Friday 17 May 2024

Old Settlers At The Mogadishu Savoy Bar

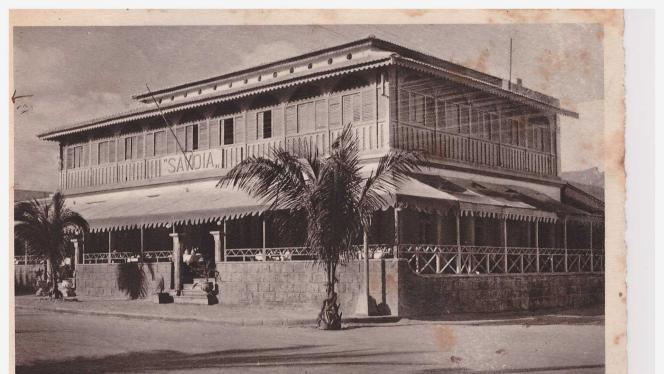

For a long time he had been the manager of all of these properties, including the many villas and the banana plantation owned by his Italian uncle. Then, he became the owner after Uncle Giovanni nominated him as his only heir. But that is another story. Indeed, it could be the prologue to the story of Giovanni, the Italian uncle of the Minister and Member of Parliament, one of the elderly Italian concessionaires whose favourite afternoon hangout was the Savoy Bar in the centre of Mogadishu, opposite the Bank.

His old friends at the Savoy bar, the octogenarians who were so proud of their wealth which, however, was almost entirely due to the work and sweat of local peasants, were suddenly horrified by Giovanni’s transfer of all his possessions to the “nephew”. Especially horrified, were those who had employed the same peasants for so long in their banana plantations. They felt an inexpressible regret for not having left anything to those who had worked so hard for their profit, while Giovanni was able to both profit and contribute to the social advancement and education of those around him.

The unhappy were not only at the Savoy Bar, however. Discontent among the Italians of Mogadishu was manifest when they found out that the old Giovanni, still alive, was leaving nearly all of his possessions into the hands of the “nephew”, son of the brother of that indigenous wife who they had never accepted. Several of them had native women as mistresses, so the behaviour of Giovanni was hazardous according to their way of thinking and their understanding of relationships with Indigenes, as they called the local population.

The Church, the Bishop, the priests all discouraged relationships between Italians and the women of the country, but what did priests and bishops know about their biological needs? The uncontainable desire that the colonist felt at the sight of a beautiful young girl, black or brown, and in bloom? It was hard to obey the Bishop’s moral dictum in the Colony. What did he know about love? Seldom had it blossomed in the heart of the colonist, but the charm of the black Ocean Venus made them deaf to the priests’ sermons. Let those ignorant Italians who came to the colony with their wives heed his sermons, as they did not know that what they could find here was better than their own. Leave the turgid bosom and incense perfumed body of the indigenous for the rest of us, thought the smart and the bachelors, while a sad Penelope waits up there for us in the cold land of the North. Wasn’t winning an ebony maiden an achievement worthy of an italic Legion? Lovers yes, but considering them as wives, and therefore deserving of being joint owners, was just not acceptable for these men who always behaved with a very colonial attitude and were imbued with the myth of Imperial conquest. For goodness sake! These old settlers wouldn’t ever consider being co-owners with these women they were living with, let alone acknowledge their many relatives. As such, the relatives of their local women had to remain strangers to the ownership of their properties.

The old settlers often spoke with one another about these things. John, when his countrymen would ask him openly why he’d put everything in the hands of someone not of his blood, would respond with a sarcastic tone, "I only had a colonial uniform when I first stepped foot in this country, don't forget." He was right. “After a lifetime of living in this land,” he used to tell them, “And now that I have become rich and elderly, who should I leave the things that I created with my family, if not to its members?” They didn't know what to answer him. Indeed, he was right about his family too. The brothers, sisters, and the many grandchildren of the woman with whom he lived for so long a time, these were his family. The other Italians called him “The Somali”. This did not bother him at all, in fact, he liked to be called that. His reply to this had always been, “I have not become Somali by paper and stamps on documents, but with spirit and a long service in this country, even before the birth of this Somali Republic still in its cradle.” In the quiet town of Mogadishu in the early sixties, the old colonial soldier, who then became a concessionaire and a colonial bureaucrat during the Fascist period, and a local administrator during the Trusteeship period before independence, was leading the life of a Somali patriarch with a brood of grandchildren, sons of brothers-in-law and sisters-in-law, and second degree relatives of his beloved wife. He felt surrounded by the love of a multitude of people. He considered all of his wife’s relatives as his own natural relatives. He felt at ease with them and the land that he had long ago chosen as his abode.

The farm and the plantation created by him were making good profits. He did not get a concession after becoming a militant fascist (out of conviction, not convenience, he liked to point out when at the patio of Café Savoy to the old colonials like him gathered around the tea tables), but before fascism. Giovanni was a romagnolo, determined, apparently rude and tenacious, as those of his land generally are, but with a tender heart. He was a man that for more than three quarters of his life lived in Somalia. “A piece of Somalia’s history”, as a famous scholar of Somalia who left a monumental work once defined him. Giovanni had always admitted that he had been a fascist once, and he was the only one to do so openly in Mogadishu on the threshold of a post-colonial era. Indeed, he became fascist only in the Colony. He was already here when this thing called fascism forcefully entered into the lives of the Italians. In the early 1920s Giovanni became a fascist only because Mussolini, the leader of fascism in Italy, was from his own region, a romagnolo like himself. He is one you can believe in, he thought, because people like him never forget their peasant origins and agricultural roots. And here in the Colony, people like that were needed most, hardworking and disciplined people who can love the land and that can make it a prosperous country. That was what fascism was promising and what Giovanni was ready to accept, an agrarian society whose ideal was the eradication of poverty and idleness, also in the Italian Colonies, including Somalia. Many others adhered to this ideology when it was useful for them, then rejected it after they benefitted from it. He never did that, because he adhered to the ideals and not to the political regime and its militaristic attitude.

Among the old settlers in Mogadishu, few had the courage to admit their adherence to fascism. Some of them were also trying to hide under the enrolment of old and combative political parties in Italy which also came to establish their own offices in Mogadishu at the end of the world war. Some of them were strongly rejecting having been militants in the fascist movement in the Colony or justifying themselves by saying it was a necessity at the time if one wanted to protect his property and wellbeing. Giovanni was not rejecting or hiding anything. Conversely, he was openly admitting the fact that he had been a convinced fascist, at least before the Abyssinian war in 1935, in which he participated as an official commanding militiamen in a sector. “My entire work and commitment were about the advancement of this country and its people preceded fascism. You should know that. The people of this country know that”, he often sustained. In his earlier youth when he came to the Colony, he dreamt of being part of the builders of a new Colony on the shores of the Indian Ocean where the local population and new settlers could live in harmony. Had he accomplished that ideal of a place? On this, his own point of view was, “I have no regrets, nothing at all, because I always worked together with, and with respect of, the local population, giving them their fair share of what I produced with them and, more importantly, strengthened their cultural identity as a nation.” He would say this while sitting at the tables of the Savoy Bar with some of the Italian colonial settlers of Mogadishu. Sometimes, proudly enough, he would tell his friends with a certain sense of accomplishment, “I think I have succeeded in making my workers love working in the same way that the people of the place I come from love it.” Some other times, tastefully sipping the spiced aromatic Somali tea, you could hear him sarcastically saying, “This country is on his own feet now, thanks to our hard work yes, but also with our worst vices!”, with the last part referring to how some Somali youth were showing interest in luxury consumptions like smoking brand cigarettes and night clubs with all the imaginable consequences to customs and behaviours.

“I am an elderly man now,” he told those who invited him to join their own political parties because of his prestige both among the Italians and the Somalis during the end of the Italian trusteeship administration in Somalia. The age of ardour and passion had gone, he would reply to those responsible of the political parties of the new and democratic Italy in Somalia. His role in the administration was commanding him to be above all the parties. The ten year period of the Italian trusteeship administration, which started in 1950, had come to its end very rapidly, different from the previous twenty years of the fascist colonial administration in Somalia which were terribly heavy and turbulent years. It was thought, in fact, that the trusteeship tenure would mitigate the horrible misdemeanours of a half a century before. However, according to some, creating democratic institutions in ten years was logically absurd, given the experience of the colonial administration which had not promoted or encouraged education among the Somalis and the subsequent trusteeship administration which was ineffectual for a while. Also Giovanni came to believe that to create such institutions, which were essential to transform the country, massive efforts and dedication to democratic ideals were needed. When Giovanni was loudly and openly voicing such an opinion, was called “Fascista!” by many. He knew that they were not worthy a reply.

However, for some settlers, the post-war Italian government’s public funding had been useful in getting their economic activities back on their feet, and for some others to create new and profitable enterprises, mostly in Mogadishu. In one way or another, the former settlers and business entrepreneurs in the city were strongly willing to survive the upcoming independence of the country. Survive! Such was the spirit of the times, for those Italians who had chosen to remain in the new Somalia. No more were there dreams of “the Colony” on the shores of the Indian Ocean or their own “place in the sun”, but a new political reality towards which they were nurturing hope and fear at the same time. From afar, the people in the government in Rome had a political vision in perspective. There were economic perspectives in the banana sector that could contribute both to the development of the agricultural sector in Somalia with a secure market in Italy, but more importantly to the profit of well-organized investors. The Italian settlers and business community in Mogadishu could be their link to the new country’s leadership. In particular, those long-time Italian residents, former bureaucrats and colonial administrators. In other words, people like Giovanni who had been an exemplary commissioner during the trusteeship administration and with very in depth knowledge of the country and its social particularities were indispensable and should remain in Somalia.

Giovanni had come in the Colony in the wake of Governor De Martino back in 1910. For a long time, he had been one of the few people who could speak the local language. His peasant agricultural roots had helped him in connecting and communicating with the local population and to easily understand their culture. The ability to relate to the culture earned him the role of local militia commander. During the first decade of his permanence in the Colony, he occupied that role and had the opportunity to share with his men long and exhaustive marches in the savannah to explore and eventually to secure peace among the tribes within the borders of the Colony. That experience gave him a unique perspective of the country and its population.

Among the elderly Somalis, Giovanni had a number of acquaintances and long-time friends. Many of these men have been troopers under his command in the Colonial Border Militia, as they were known then, before the De Vecchi arrival in the Colony. From time to time, one of these old friends would come to visit him in his villa in Mogadishu. He would receive the guest wholeheartedly. During those few days that his friend was his guest, Giovanni would postpone all appointments with the other old settlers at the Savoy bar. He would be in conversation with the Somali friend who would inform him and update him about the events in the provinces, the conflicts between clans as well as the subsequent peace covenants. Therefore, he thought that coven of settlers could wait as long as they wished. Giovanni had always been interested in following events, even in the most remote parts of the country. Now that he had the opportunity to know more elements of novelty regarding what was happening in the country from his Somali friend, he had no intention to waste his time at the Savoy bar with people that he could see regularly. He was one of the few Italians who extensively comprehended the intricate system of clan relationships in the country. A system which the colonial authorities of the time foresaw as an important instrument for governing a disjointed society. Giovanni had been among those colonial officials who, in early times, was responsible for the appointment and the payments of the tribal and clan chiefs without whose help, governing the unruly country would not have been possible.

With the passing of time, the Italian banana plantation owners were becoming fewer and fewer in Mogadishu. Tables at the Savoy bar which once were usually reserved to them, were now occupied by Somali politicians, bureaucrats of the former administration, former local militia men, elders and tribal chiefs mostly from the northern British Protectorate territories, and business people. This variegated humanity became now the assiduous guests of the Savoy Bar. The somnolent coven of Italian settlers were becoming now a minority among the recalcitrant multitude.

Mogadishu was not recognizable anymore even to its own historical inhabitants. It was changing very fast, extending its borders not only along the costal line, but also towards the inland, in the direction of the agricultural surroundings and to the Shabelle River. The old city with its Arabian style buildings of Shingani and Hamar-Weyne, and with the more recent colonial architecture like the newly created Assembly building which once was the Casa del Fascio, the Cathedral, the Arba’a Rukn Mosque and the Garesa of the Zanzibari sultans who ceded the coastal towns (Mogadishu included) to the Italians in a lucrative exchange without knowledge of the inhabitants, and ending up to the Martini Hospital on the coast and the Forte Cecchi overlaying the Gubernatorial Place. Two main roads ran along this old Mogadishu. One was the Lungomare which connected, from south to north, The Campo Bottego and the Lido, passing through the Hamar-Weyne market. The second road, parallel to the first, was The Strada Imperiale from the Casa del Fascio to Villa Abruzzi, passing through the Villaggio Arabo (Arab Village). Beyond that point there were the houses of the newly extending suburbs of the city. The arish houses and the verandas in the peripheral parts of the city were areas unknown to the Italians who would never dare to venture within. Not because these particular spaces were much more dangerous for them, but they were spaces inhabited by a humanity which was separated by the style of living of those few Italians still remaining in Somalia, even after the end of the Fascism and colonial administration in consequence of the Italian defeat in the war of Abyssinia and their loss of Somalia to the British. In reality, the reason was that the general feeling of most of them changed after the events of 1948, when Italian residents in Mogadishu were attacked by an angry mob which was participating in the demonstrations organized to show the United Nations envois’ the rejection of an Italian return and the popular desire for the independence of the country. From that time onward, they became distrusting and reclusive, staying inside their inner-city circles, like the Casa d’Italia, La Cattedrale, Cartolibreria Porro, Cinema Missione, Croce del Sud, Bar Savoia, Cappuccetto Nero and Il Lido di Mogadiscio (The Mogadishu Beach).

In the eve of independence, many Italian settlers and banana plantation owners sent their children to Italy to study there, as they were claiming. However, after finishing their studies those children continued their staying in their fatherland country. Only a few of them would come back to Mogadishu. In early 1960s the banana industry was more profitable than ever for the settlers, because of a protected regime of importation accorded by the Italian government. This lucrative concession was the main factor which was holding the settlers to Somalia. That favourable commercial agreement was guaranteeing Somali bananas with both an exclusive market in Italy and consistent financial support which were prompting Italian settlers’ dreams in an era of prosperity in the African country even after the demise of the Italian colonial power in Somalia.

Local agriculturalists in the banana sector were very few in number, almost inexistent. The Italian settlers did not have a financial problem, but they did have another kind of problem, that is, the age decline in the settler community. The majority of them were over their 70s. Their children, in fact, did not have the same passion of their fathers and the desire to practice agriculture in a country which was becoming independent from its former colonial power and with evident need to feed its population, not by bananas but by cereals. These children who were brought up and educated differently from their fathers, would not have the intention to stop the history and the passing of time, setting it back in colonial era. Many of them were preferring to stay in Italy, instead of coming back to the new Somalia. The elderly settlers were continuing their struggle to prosper in a sector that the Italian government was indirectly sustaining with huge financial contributions. However, they knew they were subdued by age, without the perspective to hand over the banana plantations to their heirs to continue what they had started up in colonial times. Despite their old age and their situation under the equator, most of them were still working in their plantations. Vigorous and hardworking, it is fair to admit. As long as there is life one must work! That was their motto.

In the settlers’ mentality the idea of retirement due to age did not exist. Indeed, as it was sustained by Pietro, the mechanic who was living in his garage surrounded by scrapped cars and tractors, for them to retire because of age would be the equivalent to state that one is no more useful in any way, that is, to stop living as human being. The elderly settlers knew this fact, so no one of them would stop working and retire. Despite their old age, they would obstinately continue working very hard. Pietro was part of the group and he was the one who would repair every mechanical component the settlers were using in their relatively mechanized plantations as well as their own Campagnola cars, a kind of Italian made Jeep. The equatorial sun was making them feel full of vitality. They were growing older, that was sure, but they enjoyed good health, prosperous economic conditions and they were continuously working, though with less hard tasks in respect to the times of their youthful years. Inexorable time that consumes everything! Yet, the weakened physical strength in them was replaced by the wisdom of mature age.

In those 1950s, within the Italian settlers and the business community in Somalia, a feeling of insecurity towards the imminent transfer of power to a Somali authority was permeating. That sentiment of uncertainty about what would happen to their permanence in the country and their properties was steadily growing with the passing of months. There were also those who were spreading voices of nationalization of economic and financial assets or of their transfer to locals. These voices were aggravating the anxiety felt by the members of the Italian community of Mogadishu, mostly within the plantation owners whose attachment to the land was strong and passionate. Some of them had already started to parcel the property and proceeded the handover to their acquired relatives in order to preserve it from an eventual nationalization. In doing so they were trying to adopt new strategies of survival in a changing political environment. Some of them would find their way in associating themselves with emerging political figures in the new local institutions and by this they would shield themselves from any nationalization of their assets and ownership. Some others were weighing out the idea of a “prestanome” for their properties, that is, a fake owner, a person of trust who will not create problems later on. By the end of the 1950s, most of them found the arrangements they needed, mostly amongst friends and acquired-relatives. The latter, as many were saying, were prepared to substitute the Italians as a privileged class in the new Somalia to come. From this time on, the Italian settlers and plantation owners were limiting their commitment and daily work in their properties as most of the management tasks were now passing to the new “owners” by trust. At last, the settlers would find the time to enjoy good-time in conversation with friends at the “Bar Savoia” in front of their aromatic Somali tea, savoring the breeze from the sea on the Benadir coast. Although most of their time was spent between the Italian Club and the Savoy bar, they still went to the plantations, though without carrying out activities they used to. They were helping the workers with suggestions while walking through the rows of banana trees, breathing the healthy air to which their lungs were long accustomed. Often they were giving a hand in the process of packaging the bananas for export. That gave a sense to their life and existence. In no way were they feeling as retired elderly people or useless human beings under this equatorial sun. For this, some of them were grateful to Mussolini and to those who had claimed for them “a spot in the sun”.

During those excursions into the plantations, they would talk with the overseers in which they trusted. The latter once used to go around with the whips to scare the new peasants at work, but they later abandoned that old custom and had substituted it with a new one consisting in voicing their orders with an intimidating tone. In that way they could force the poor peasants to work harder and relentlessly. Sometimes children were also at work in the plantations. With the task of cutting bunches of bananas from a tree, or transporting them to the sheltered space for the washing basin and the packaging tables. Some other times, they were helping the people who loaded the heavy banana packages onto the trucks, ready to depart towards the port where the ship which would take them to Italy was anchored, or to the depot for distribution to the local markets. The majority of those who were working as peasants in the Italian concessions now were local small farmers who previously were expropriated by the colonial government which then gave their land to the newly arrived Italian settlers in line with the Fascist colonial policy for the development of the Benadir agricultural sector. Many of the peasants were working in the plantations since a young age, in conditions not unlike those of servitude. Only few in number had their own small plots of land where they were growing some maize and other crops such as vegetables inadequate for their own sustenance. So, deprived of their own land and reduced to landless peasants, they were merely surviving with the meagre income of the wage offered to them in exchange for their labour. The children could not go to school which, anyway, there was not. The same for their parents who did not have any opportunity for schooling. The luckier ones could only go to the Koranic school, but even then, not regularly as their hands were needed to work next to their parents. The more hands were at work, the higher the wages that could be received and the settlers were happy with this situation of their labourers. Now people were rushing from very part of the country just for that miserable wage, especially during drought times when entire villages would be abandoned to settle in the proximity of the Italian plantations. The latter would not need to resort to the forced labour system introduced by the Italian colonial authority in the Southern Somalia any more, the work-force were there, available in abundance for a small wage.

The elderly settlers and owners of banana plantations who remained in Somalia were enjoying their time in Mogadishu. Notwithstanding the fact that they were agriculturalists by profession, they owned most of the buildings in the centre of the city. Some of them also owned commercial enterprises. The British administration which followed the demise of the fascist colonial administration in Southern Somalia, did deprive but few of their colonial privileges, only those which were incompatible with the new policy. Their lives were evolving within the boundaries of the old and the commercial city, whose streets and pathways they knew as well as their own pockets, and the plantations kilometres away from the city. Their movements in the city were limited to a few places, like the Bar Savoia, the Lido and the Casa d’Italia and, once a week, the Cartoleria Porro to pick up the daily newspapers arriving from Italy. They had but few occasions to be in contact with the local Somalis. In a certain way, their world was apart, a reclusive one which was inaccessible to other people except for the Somali domestic servants.

The road from Mogadishu to Afgoi, Genale, Vittorio d’Africa and Merca had been continuously travelled by the Jeeps of the Italian settlers who were going to their plantations in those localities. The sahariana with shorts, long socks that reached till under the knee, suede shoes and a hat were their preferred work clothing. Though they had Somali chauffeurs at their service, they preferred driving by themselves on those occasions. They usually used small and beautiful Italian cars in the city, but only strong and powerful Land Rovers for their excursions towards the plantations. Accompanied by their Somali chauffeurs whose tasks were the manual reparations in cases in which that would happen to be necessary, they occasionally would stop along the way, in the open countryside, at the sight of a gazelle or some other animal of the rich fauna of Somalia. The settler, who was always was armed with a gun, would suddenly take aim of the animal and fired. As he was always trained in that sporting activity, he would always make the target. Happy with his ability with fire-arms, with the help of the young chauffeur, he then would load the animal on the rear of jeep. “Am I bravo?” He would ask to the young Somali man. “Yes, Signor Mario! You have been very much bravo.” The young man would reply to the settler. The latter, satisfied by the young man’s answer, would also say, “One must have shooter’s eye! Ahmed, would you tell everybody at the plantation, will you?” Ahmed, who was not very happy about the shooting to the gazelle, would say: “Yes, sure, I will tell to everybody at the plantation, so that they should know that Signor Mario shoots”. And ironically whispering to himself, “Luckily only the gazelles!” No, Signor Mario would not shoot to anybody, Ahmed thought, even if he wasn’t too sure about that. In some moments he was assailed by doubt about the possibility that Mario could shoot someone as he did with the gazelle. Behind the doubt, we know, lies the thought, and thought often leads to action and rebellion. Woe to Ahmed if Mario, or Antonio, had known what he was thinking! According to them, the native, as the Somali was once called, should never have thought. The only thing he had to do was to obey the orders of those who thought for him, a Mario or Antonio, and work hard with his hands, never with his head. But now the times were changing and Ahmed already had the power to think for himself, with his own head. Ahmed, indeed, secretly had his own thoughts. He would have nodded at every nonsense said by his boss and would smile. As dull as much as a painful smile, all for him. The important thing was to make the boss satisfied. The broken Italian of his employees was another thing that made the settler proud of his own status.

The employees used to avoid speaking Italian correctly to pander him, and so to please him, for he really believed that their intellectual ability was directly related to their proficiency in his language. To give them an opportunity for education was his least wish. He was just giving them some technical ability to perform the tasks he needed for his plantation, which however would not imply higher wages for them. Such had always been the settlers’ unwritten rule, and in no way could a Mario break that rule, which had its source in the colonial agricultural policy in the Benadir. Such a policy would encourage to impose and maintain a rigid separation, differentiation and degrees of privileges within the dominated colonial society. Indeed, the burden of the colonial policy would have subjugated the local agricultural population more than the rest of the entire population of the Benadir. Both pastoralists and urban dwellers were given a certain autonomy and no interference in their properties and livelihood practices. Because of colonial intervention, agricultural populations, who before colonial rule enjoyed higher levels of living conditions and independence, were now reduced to poor peasantry in the settlers’ plantations. They had lost their land properties as well as their own autonomy as individuals and communities in favour of the Italian settlers.

The settlers' age-old prejudices against the local peasants working in their plantations, according to which they considered the peasants as poor and ignorant, were still alive even by the end of the Italian colonial administration. Giovanni was aware of that situation. Not only so, but he knew how those peasants had been deprived of their land and how, by consequence of that colonial action, they had been reduced to their present conditions of peasantry.

In Mogadishu, as well as in the provincial towns, the Italians were living as if they were in a separate world, however, insufficient at sustaining itself on its own means without the services offered by locals. Giovanni was one of these settlers, owner of a banana plantation in the Benadir, in a place not far from Mogadishu. However, he was completely different from the majority of the settlers. By experience he knew how important the reciprocity with the local population was. As a result of his long time association with the Somali society, he did not share with the settlers those colonial prejudices against the local population anymore. Rather, he was very involved in Somali society, for which he nurtured a great respect. He always had few shared values with the Italian community, in particular with those he considered as newcomers, that is, those who came to Somalia only after Fascism and the Empire. The sorts of people who demonstrated, in every circumstance, a militaristic style and behaviour to make the local population feel intimidated and subjugated. He had been in the army before Fascism and before their coming the Colony. He knew the wars that they did not know very well, for he had fought in them to conquer territories for the Empire. The Empire for the Savoy Royal House. For many years now Giovanni had interrogated himself if it was worth it. Sometimes events happened elusively, to be able to make our judgement. That was the only justification he could come up with. Marshall Graziani under whose command he had been fighting during the battle of Neghelle and who he considered a good strategist, had deluded him after the conquest of Addis Ababa. At that precise time, he suddenly understood that they were fighting only for revenge, for the lost battle of Adwa, some fifty years before! From that time on, he had been against all wars, which he considered games for bored people sitting in their lounges. As for what concerned fire arms, with which the many Marios and Antonios flaunted like children’s toys, his opinion was that they should all be destroyed. For Giovanni the only fire-arm he possessed was his intelligence.

Giovanni was a person with highly human values, because of his various and rich experience in life. He had a great deal of ability to understand each person, including the locals. That was an acquired wisdom from a long time of work with the colonial administration in Somalia. In his plantation, both young and old people were at work, men and women, but the environment had always been almost serene, without shouting or reprimands. Everybody did their job, even without supervisor’s orders. Giovanni knew and understood the ability and needs of each worker in his plantation. He used to address each of them by name with respect, differently from all other settlers who always acted arrogantly against the people working in their plantations. For many years Giovanni was taking care of the education of the children of the workers of his plantation. He even had opened a school with some elementary classes, where the children were learning how to read, write and basic arithmetic, after which he would help them to enrol in the closest mission school. Already, a dozen of those children in whose education he invested, had become technicians and artisans with their own professions. He perceived the inevitability of the changing of times, more than any other settler in the country. In consequence of that understanding, he often had been questioning himself about their presence in a place that had once been their Colony, but that would now be proceeding towards its own independence, to become a sovereign nation. Such reflections more than often would conduct his thoughts to his own personal past, asking himself, for example, if he had contributed enough to the progress and development of the people of the country. That was Giovanni, an exceptional man among the Italian plantation owners in the Benadir, narrow-minded but hardworking people who were living in Mogadishu, the Pearl of Indian Ocean, in their golden isolation from the rest of its inhabitants.

It is Giovanni’s story that we wanted to discern from that sordid and insular living of the restricted circle of Italian settlers in Somalia. His story intertwines with the larger history of Italian colonialism in Somalia. It becomes part of the history of the birth of a new state in Africa, still the history of postcolonial generations to come.