Tuesday 22 October 2024

How We Walk…Politically

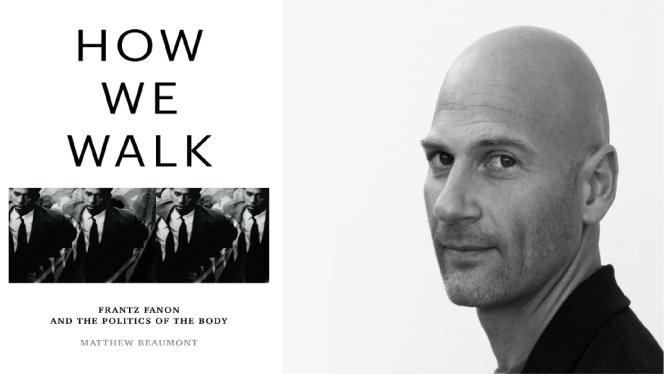

Matthew Beaumont, a scholar of English literature at UCL, engaged in a thought-provoking discussion with Geeska about his groundbreaking new book on Fanon, racism and why walking is political.

In his Confessions, the eighteenth-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote: “I can only meditate when I am walking. When I stop, I cease to think; my mind only works with my legs.” A young Nietzche also celebrated the virtues of walking, declaring it, alongside Schumann’s music and Schopenhauer’s literary work, to be his greatest source of recreation. In her book, Wanderlust, American writer Rebecca Solnit said “Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and many others walked far, and Thomas Hobbes even had a walking stick with an inkhorn built into it so he could jot down ideas as he went.” Djiboutian author, Abdourahman Waberi, also drew inspiration for his recent book, Why Do You Dance When You Walk, about life with a disability, during a stroll with his daughter.

Walking has always played a greater role in human history than its practical purpose, providing some of our greatest thinkers with a conduit to explore some of our most pressing questions. In that regard, it is also political, says Matthew Beaumont, a scholar of English literature at the University College London, in his new book How We Walk. Beaumont challenges us to reconsider walking, drawing on Fanon’s exploration of the politics of walking while black, Reich’s belief in the revealing nature of posture and gait, and Bloch’s vision of walking as a symbol of liberation inviting us to rethink our understanding of this seemingly “natural” activity. Beaumont cautions against taking walking for granted, emphasising how our movements are shaped by social, cultural, and genetic factors.

Beaumont’s research goes beyond a dispassionate examination of the topic; however, he urges us to confront the racism and classism embedded in our society through the lens of an otherwise mundane activity. As a black man from Africa, I found this conversation and the insights shared by Professor Beaumont to be both enlightening and empowering. It is through engaging with works like How We Walk that we can begin to unravel the connections between our bodies, our identities, and the world around us.

In this interview, Prof. Beaumont engaged in a thought-provoking discussion with Geeska about his groundbreaking new book on Fanon, racism and why walking is political.

Abdiaziz Mahdi (AM): The first question on the minds of readers delving into your literary works (including Nightwalking, The Walker, and your latest masterpiece, How We Walk) is: why walking? Why does walking, a seemingly mundane activity, warrant a serious critical and academic examination? Why is walking not a neutral activity?

Matthew Beaumont (MB): It’s a good question! We tend to take walking – as an activity – for granted. Like breathing. We assume these activities are ‘natural’. Now, it’s true that these are ‘natural’ activities, in that they are a core part of what Marx called our ‘species being’. But, as such, they are mediated by culture. So, they are never simply ‘natural’. The French anthropologist Marcel Mauss, whom Frantz Fanon admired, referred to what he called ‘techniques of the body’, and walking is one of these. The way one walks is shaped by the social and cultural conditions one inhabits, as well as by one’s genetics. As Mauss said, ‘the positions of the arms and hands while walking form a social idiosyncrasy, they are not simply a product of some purely individual, almost completely psychical arrangements and mechanisms’. I am very interested in this idea of gait – the organisation of one’s arms and legs when one is walking – as a ‘social idiosyncrasy’. What might this idiosyncrasy tell us about society?

Fanon is, I think, interested in the politics of the standing, walking body. It is related, in fact, to his interest in the politics of breathing. Breathing, as I mentioned, is a natural activity that is culturally mediated and therefore political. This has become apparent recently in two contexts. One is the Covid-19 pandemic. The Cameroonian political philosopher Achille Mbembe – who is, incidentally, a penetrating reader of Fanon – wrote an interesting piece on this theme, ‘The Universal Right to Breathe’. There, thinking of the logic of racial capitalism, he called for a critique of ‘everything that condemns the majority of humankind to a premature cessation of breathing, everything that fundamentally attacks the respiratory tract’. This oppressive situation, endemic to racial capitalism as a system, was of course dramatically exacerbated by the pandemic. So that’s one important context. The other is the murder of George Floyd in 2020, when a racist police officer in Minneapolis knelt on his neck and killed him, since his last words, notoriously, were ‘I can’t breathe’. This then became the slogan of the Black Lives Matter movement.

If breathing is political, as these differing but overlapping events make apparent, then so is walking. As a psychiatrist and political activist, Fanon developed an interest not only in what he called ‘occupied breathing’ – that is, breathing under the conditions of colonisation – but what I think of as occupied walking. In a racist or colonialist society, the way the colonised or racialised walk the streets is shaped by the need to defend themselves, both consciously and unconsciously, against the police or an occupying army, or even simply the surveillance system that is an extension of these powers. As Fanon insisted, the colonised subject lives with permanently tensed muscles, and this imprints colonialism on their body and its characteristic movements.

AM: You have eloquently pointed out the inherent politics in the act of walking. As humans, we are undeniably political beings. How does our very movement, our physical bodies, reflect and embody this political identity?

MB: So let me briefly offer slightly more detail. Perhaps the easiest way of doing so is by citing the experience of the Jamaican journalist Garnette Cadogan, who wrote an influential article in 2016 entitled ‘Walking While Black’. There, he wrote about what it was like to move from Jamaica, where he had never felt self-conscious about walking in the streets, to the US. In New Orleans, New York, and other cities, he suddenly realised that walking was an intensely political activity. He could no longer take for granted the apparently simple act of putting one leg in front of the other, because as a Black man he was effectively criminalised for exercising the freedom to walk along the street. He was threatened, attacked, and arrested.

In his article, Cadogan identifies this experience as one of infantilisation – his fears of being policed and prosecuted had the effect of projecting him back into his past, specifically that process whereby he had learned to walk as a small child. Why? Because walking had suddenly once again become a painfully self-conscious, effortful activity, one fraught with potential danger. ‘As a black adult,’ Cadogan states in this piece, ‘I am often returned to that moment in childhood when I’m just learning to walk. I am once again on high alert, vigilant.’

The Black subject, according to Cadogan, is objectified by the gaze of white passers-by; or, more perniciously still, that of representatives of the state and its surveillance technologies. And, in some basic sense, the Black subject is thus not simply made to feel self-conscious – ‘cripplingly’ self-conscious in the colloquial phrase in English – but denied agency, subjectivity. They are rejected and rendered abject.

This loss of subjecthood, this state of abjecthood, if I can put it like that, is inscribed on the body. Instead of walking freely, relaxedly and with confidence, the Black subject’s movements are restrained and inhibited. And their muscles, as Fanon repeatedly notes, are tensed.

AM: The enduring fascination with studying Frantz Fanon persists, with scholars like Hussein M Adam exploring Fanon as a democratic political theorist and Fatima Scek delving into the intriguing topic of “Fanon and Hair.” Your unique contribution to this discourse, analysing the politics of the body and walking through a Fanonian lens, sheds new light on this iconic thinker. How do we not only view Fanon as a profound intellectual, but also as a subject of scholarly inquiry?

MB: As you imply, Fanon is a popular figure not simply because he is politically inspiring but because his writings repay close analysis from all sorts of different disciplinary perspectives. Of course, there is a danger here. Fanon is the subject of thousands of academic articles, books, and dissertations, and at least some of these have the effect, intentional or not, of domesticating or depoliticising him. I’m conscious that my own work on Fanon and the politics of the body, which necessarily leans on the often-brilliant scholarship that precedes it, is not immune to this criticism. And I’m conscious that, as a white man writing about Fanon’s account of the alienation and distortion of racialized bodies in imperial and colonial societies, I am not speaking from personal experience. As I say in my preface to the book, quoting the critic Nicholas Mirzoeff, I’m not speaking for Black experience but against anti-blackness.

But I hope that in some respects I’m nonetheless resisting the depoliticization of Fanon that took place under the auspices of post-structuralism back in the 1980s and 1990s. This is in part the point of returning to the body – not the libidinal body of the post-modernists but the labouring body. I wanted the book to give a sense of the physicality and corporeality of Fanon’s language as well as his politics. This is also in part the point of the dialogues that I set up in the book between Fanon and other thinkers on the Left, above all the German Marxist Ernst Bloch and the Austrian Freudian-Marxist Wilhelm Reich. The latter figure is especially important, I think, because Fanon read him. Reich’s notion of ‘character armour’, of the way the body and psyche are shaped and distorted by alienation, was I suspect crucial to Fanon, though so far as I know nobody has made this connection before me.

AM: Your meticulous examination reveals that walking while Black is inherently political. Can you provide insight into the interconnectedness of race (and class) with walking in a world characterised by Manichean divisions, as described by Fanon?

MB: Yes – the way one carries one’s body under the everyday conditions of racial capitalism is shaped by class as well as race (and, of course, the politics of gender). This was something that Marx and Engels themselves recognised. In Capital, Marx identifies some of the illnesses and disabilities that the industrial system induces in its labourers, and he refers to what he calls ‘industrial pathology’. Engels, in The Condition of the Working Class in England, lists many of these, including ‘flattening of the foot’, swollen joints and varicose veins.

Fanon inherits this tradition, I think. He talked of the need to ‘stretch’ Marxism, and one of the ways he himself did so was by extending and sophisticating Marxism’s insights into the oppressed body, principally by exploring the impact of colonialism and racial capitalism on this body. As a trained doctor, he was of course in a privileged position to do this. For example, he too mentions varicose veins. In Black Skin, White Masks, he bitterly attacks French doctors who see varicose veins merely as the result of constitutional weakness. Instead, Fanon argues, varicose veins are the result of conditions of production in which workers, especially colonised ones, are forced to spend ten hours a day on their feet. It is impossible to abstract questions of race and class from discussion of the body’s functioning or malfunctioning.

AM: In Somali culture, a powerful saying warns against walking with borrowed limbs, emphasising the importance of ownership. (The adage goes: “You can’t walk for more than six steps while using limbs that don’t belong to you”, laafyo aan loo dhalani lix tallaabo ma dhaafaan). When juxtaposed with Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks, and your own work in How We Walk (particularly chapters 1 to 4), the question arises: what happens when we relinquish our agency and adopt the limbs of the oppressor? How does this act of imitation impact our identity and autonomy?

MB: That is a wonderful saying! I like its affirmation of autonomy and agency. And it is true that adopting the limbs of the oppressor, as you put it, is paradoxically disabling. To internalise the oppressor’s logic of mobility, or immobility, is politically damaging. In the book, I often speak of ‘demobilisation’, by which I mean, first, the immobilisation that racial and colonial capitalism induce in those they alienate or exploit; and second, the sort of political paralysis that is analogous to the condition of an army which has been demobilised or ‘stood down’. Racial capitalism immobilises its subjects in both these senses.

I would say, however, in opposition to the saying you have quoted, that there is a sense in which, to walk at all, we do in fact need the limbs of others. Think of the infant who learns to walk and who must lean on its parent’s arm or hold their hands. Or the elderly person who needs physical support to walk. Perhaps at one level there is no shame in the loss of autonomy that this entails. Perhaps we can only walk more than six steps while using – or at least relying on – limbs that don’t belong to us. Politically speaking, this co-dependency is, potentially, the basis of solidarity and collective action.

AM: As I delved into the pages of your book, one question lingered in my mind: In a world plagued by different forms of oppression and dehumanisation, can walking serve as a form of decolonization and de-alienation? To paraphrase Albert Camus, could the simple act of walking freely be the most powerful way to confront an unfree world, transforming each step into a rebellious act?

MB: In itself, walking is not a political programme. I like the Surrealist André Breton’s claim that the footstep is an emblem of the ‘free everyday’, but in truth any act of walking, however assertive or creative, is fatally limited unless it is related to a broader political movement for emancipation. As part of such a movement, however, it can be very radical. Think of the long history of oppressed peoples who have refused to remain confined to the places in which, officially or unofficially, they have been segregated by the state. Sometimes this has appeared to involve an individual act of rebellion, but such an act is the symptomatic expression of a collective act of rebellion.

Recall the solitary rebel in Tiananmen Square in 1989 who, the day after the massacre of hundreds of protestors, heroically walked out in front of the column of tanks and blocked their path. He stood, he marched, with many others, though only he had the courage and the political imagination, at that moment, when the cameras happened to be rolling, to make himself visible and hence especially vulnerable. Perhaps, when we walk in our everyday lives, we should attempt to emulate this sort of act, albeit in circumstances that are likely to be far less extreme, thereby defying the conditions of our oppression and alienation and – as you rather beautifully put it – transforming each step into a rebellious act.

AM: So, to conclude, during my research for this interview, it became evident that you have a deep passion for walking. If I may ask, do you choose to walk even when you don’t have to, and if so, what drives you to do so?

MB: Yes! I walk incessantly! I find excuses to walk if I possibly can. It impacts minimally on the environment, it is physically healthy, and perhaps most important of all, it is mentally stimulating. I am a great believer in the dynamic relationship between walking and thinking. Walking is free but it is also freeing. Nietzsche is inspirational in this respect, because of his belief that – I am paraphrasing – philosophy itself should be written when walking. He added, ‘or, preferably, dancing’ – but it can be difficult to dance through the streets of London, where I live, without attracting the kind of attention that tends to make thinking impossible! To walk is to engage with the world in its materiality and sociality but also to liberate the imagination. It is a way of confronting the unfree world, in your excellent phrase, with a small measure of individual freedom.