Friday 1 November 2024

The British empire’s air campaign on Taleh killed and displaced thousands

Mohamoud Ibrahim (Hajji) recounts the stories of the victims of Britain’s aerial bombardment of Dervish bases in Taleh. He is also a descendant of the few survivors.

This poem is an expression of the emotions I experienced that afternoon when Al Jazeera Arabic arrived to interview me:

Xadantadii Jasiiraa

Xusuuso igu qaadhiyo

Xiisiyo ladh kiciyaye

Bal xisaabtan iga qora.

Al Jazeera’s nudging

Evokes dormant memories

Bitter recollections and longings

Transcribe from me this reckoning

At noon on June 27th, 2023, at my home in London, I received a visit from a producer working with the Arabic section of Al Jazeera. The visit had been pre-arranged, so his arrival wasn't unexpected. He was filming a program on the history of the Dervishes and asked me: “Since you hail from Taleh, what can you tell us about the history of the Dervishes?” Numerous things came to mind, but I decided to focus on the aerial bombardment and its consequences. I had but a minute. I said what I could say.

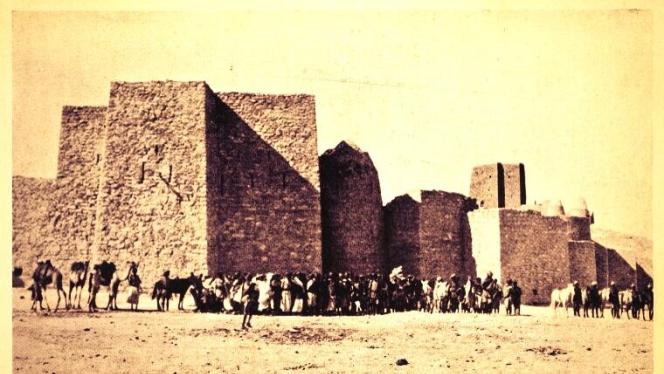

It is the end of 1919, and early 1920. From the beginning of the century, the land where Somalis lived had garnered the attention of several colonial empires who wanted secure safe passage from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean through the Suez. Mohammed Abdulle Hassan (Sayyid) was among a small number of Somalis who organised anti-imperialist revolts. The purpose of this struggle was to get rid of the white European colonialists that divided Africa. In his own words composed as part of his famous letter to England he said: “I have no forts, no houses ... I have no cultivated fields, no silver or gold for you to take… All you can get from me is war… If you wish peace, go away from my country to your own.”

Throughout the region, skirmishes erupted between the Dervishes and their adversaries. Victories and setbacks marked both sides’ endeavors, yet with each confrontation, the Dervishes grew more resolute, confident that they could not be overpowered. Their ranks swelled, and their fortifications multiplied year by year. Despite facing well-equipped foes backed by ample weapons, resources and technology, manned by both white and black, the Dervishes remained unbeaten. Mohammed Abdulle Hassan was aware of the imbalance and exhorted his followers to remain steadfast despite it: “Unbelievers have invaded you in your country, to corrupt you and to corrupt your religion, and to force you to believe their own religion, supported by their governments, their arms and their numbers. But your faith in God and in your dignity is sufficient arms. Do not, then, flee from their troops, nor from the greatness of their arms; God is stronger than they.”

At one point, the colonisers contemplated abandoning this unforgiving terrain, where their forces suffered, and resources dwindled. Yet, Allah did not decree their departure.

When the Dervishes could not be overpowered, the British decided to bomb them from the sky. The first bombardment took place in Midhasho, on the 21st of January 1920. The bombing continued throughout the next day. An RAF report said:

“The village was bombed from 1,000 to 2,000 ft; direct hits obtained on village and southern Fort; also, direct hits on stock moving eastward from the village and apparently following the riverbed in direction of Jid Ali. Machines then descended to 900 ft. and shot up dervishes and stock with good effect. Estimated amount of stock 2,000 Camels and six flock [sic] of sheep. No big movement of dervishes seen”

On the 27th of the same month, Jiidali was bombarded. Taleh, which was the main center of the Dervishes, was the target of the heaviest bombing at the beginning of February 1920. Accustomed to engaging in face-to-face combat on the battlefield, the Dervishes faced a new and devastating threat from above. A torrent of destructive fire rained down from the skies, leaving no refuge for man or beast within the fort or its environs. Those who survived rushed to leave only to find themselves encircled by troops armed with artillery, heavy weaponry, and landmines.

Those who fled the 1920 bombardment of Taleh fled in panic, scattering desperately into the open expanse. There was nowhere to seek refuge. Siblings fled in different directions, and mothers were forced to make heart-wrenching choices, leaving behind infants unable to walk to save those who could. Amid the chaos, there was no room to even consider the plight of the injured. Even if one felt sympathy, they were powerless to offer aid, each burdened by their own trials. Cries of “save me, release me,” rang out, each man preoccupied with himself as if it was the day of reckoning.

No-one was spared between Burao and Las Anod The brutality of the conflict forced thousands to flee. Some fled from the Dervishes, others from the English. Wild animals roamed everywhere, the injured and weak torn apart by them alive. Even the birds of prey showed no mercy, extending their deadly talons not only to the deceased but also to young children. These children were not strangers but beloved kin, recognized by name and likeness. Powerless to intervene, one could only watch in despair as the child clinging to your neck might soon be seized and carried aloft by predatory birds.

To compound the situation, the sun was barely descending towards its resting place when beasts appeared. It’s as though time itself had cleaved in two—the birds of prey on one side, the beasts of the land on the other! Among them, the hyenas are the most ghastly. Unlike the leopards and lions, who retain a modicum of shame in their wait for their prey’s demise, the hyena shows no such restraint. It sinks its teeth into the still-living, forcing one to contemplate which fate is preferable. It’s impossible to fully capture the experiences of those who faced the attack. One might question what those who couldn't escape, who perished on the spot, did to deserve such a fate.

The aerial bombardment was coupled with ground force. The ground forces objectives were two-fold. They wanted to act as scouts for the aircraft, surveilling dervish soldiers and centers and wanted to obliterate anything—be it people or livestock—that survived the aerial assault.

Those who remained on the ground found themselves plagued by unfamiliar diseases introduced to the region. Survivors recount tales of poisoned wells, valleys set ablaze, and the robbing of livestock. The toxins from the bombs seeped into the earth and water, leading to widespread death among humans, animals, game, and even wild creatures for years to come.

This account isn’t a fairy tale or a product of imagination. It’s a firsthand recollection from my great aunt, Hasna Dahar, who was among the children who fled the Taleh camp. Hasna was just nine years old at the time, part of a family of eleven—nine children and their parents, Dahar Bilal and Ugaso, both confirmed killed in an airstrike. Their death was instantaneous. Of the nine children, only four were later accounted for. The whereabouts of the other five remain a mystery to this day. The story of Shamis, the mother of Djiboutian writer Patrick Erouart-Siad, gives a glimpse into what became of those missing children, kidnapped by missionaries and raised Catholic in what was then French Somaliland.

What’s astonishing is that the four who survived, the oldest being 14, each embarked on separate journeys. Ali Dahar, the eldest, found refuge in Dire Dawa (current day Ethiopia), approximately 1000 km from Taleh, travelling there on foot. His descendants still reside there. Jama Dahar, who is my grandfather, settled in Bullahar, 530 km away. It was there that my father and his siblings were born. Hasna Dahar made her way to Hargeisa, covering a distance of 680 km, while Qumman continued on to Lasqoray, a journey of 500 km.

When talking about the survivors of the RAF airstrikes, my family was exceptionally fortunate—four members managed to survive. However, across the Somali population who remained loyal to the Dervishes and were present in the targeted centers survival rates were grim, often limited to one or two individuals per family. Some families were entirely eradicated. As a result, among the immediate descendants following the bombing, finding someone with a first cousin is rare. In the second generation, encountering individuals with second cousins is a rarity.

Any individual of my generation, hailing from families whose ancestors survived the bombings perpetrated by British colonialists and who lived to see their grandparents, undoubtedly possesses similar tales, if not more poignant ones. The British government, responsible for these atrocities, has yet to offer any reparations or acknowledge the massacre it inflicted. The victims have not forgotten, nor will they ever. Accountability will eventually catch up with them.