Tuesday 22 October 2024

Abdi Ismail Samatar: The new constitution is a “regressive milestone” for Somalia

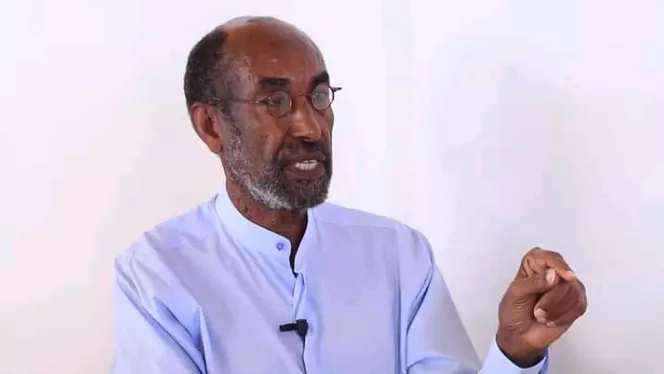

Somali scholar and senator, Abdi Ismail Samatar, says the new constitution could be a fatal step backward for the country.

On the 30th of March, Somalia held a joint session of its parliament where lawmakers from the upper and lower houses passed a bill making major revisions to the country’s constitution which among other things, empowers the president to appoint the prime minister instead of parliament and introduce a direct voting system for the public in place of the existing indirect model.

In a post on X, formerly Twitter, the speaker of Somalia’s parliament, Adan Mohamed Nur Madobe, called the passing of the motion “historic”, whilst Abdullahi Hersi Timacadde, deputy speaker of the senate, said the change was a “crucial step towards a brighter future.”

In all, 212 MPs from the 275-seat lower house and 42 of the 56 senators voted in favour. However, the changes haven’t been without their detractors. Somalia’s provisional constitution was introduced in 2012, ending the transitional government. Though heavily criticized, it had widespread buy-in among Somalia’s political elites. The decision to make major revisions to it has been met with dogged opposition from former presidents and prime ministers and crucially the federal state of Puntland.

The amendments apply to the first four chapters of the Somali constitution which deal with the structure of government, fundamental rights, land and property rights and political representation. Here are some of the standout changes:

- The president can directly appoint the prime minister without the need for parliamentary approval.

- Presidents of federal states are to be referred to as “leaders”, not “presidents”.

- Somalia will move away from the indirect clan-based method of electing its representatives and introduce universal suffrage.

- Only three political parties will be permitted in Somalia.

- The president exercises greater authority over the appointment of the election committee.

Abdi Ismail Samatar, a senator in Somalia’s upper house has been a staunch critic of the move, describing it as a “regressive milestone” which diminishes the role of parliament in public affairs. Samatar is also a professor at the University of Minnesota and at the University of Pretoria in South Africa. He is the author of several books, including Africa’s First Democrats: Somalia’s Aden A. Osman and Abdirazak H. Hussen and Framing Somalia: Beyond Africa’s Merchants of Misery.

He speaks to Geeska about the new constitution and its implications for Somalia.

Geeska: The government has pitched this change to the public and international community as a historic milestone. What are your thoughts on the changes?

Abdi Ismail Samatar: Well, it is certainly a historic moment. It is the first time in the history of Africa, not only Somalia, that parliamentary leadership and members of parliament have decided to formally give away their legislative authority to the executive branch, the president. In that sense, it is a regressive historical milestone.

Concentrating all this authority in the president, a president who has not proven to be above the fray, in terms of being just, fair and loyal to the country and constitution, makes it a remarkably regressive milestone.

Geeska: People have focused on different amendments, but which ones stand out to you?

AIS: There are several points which are terribly important. One is the diminution of the role of parliament in the management of the country’s public affairs, as I have just noted. The second is that there has not been a consensus from various political camps. Some of those camps are dysfunctional, as is the federal government, but at least if there was an effort to reach people so that there would be some degree of consensus and coherence has given this endeavour an additional liability.

Thirdly, at a time when Somalia is facing quite a menace from Ethiopia in the form of a MoU with Muse Bihi, to open a new front which could further destabilise and disorient the political trajectory of the country may be a fatal step backward.

Geeska: You’re a lawmaker yourself, could you expand a little on the implications for the relationship between the legislative and executive branches of government?

AIS: I made a remark very early on, almost two years ago and my friends said I was deeply pessimistic. But I said that this may be the worst parliament in the history of the country and perhaps the continent. What you saw yesterday is a clear manifestation of how bankrupt this parliament is. It was like a meat market yesterday.

The leadership of the two houses have betrayed their oaths in the clearest and most cruel manner possible. The leaders in both institutions have condemned their offices to becoming inconsequential in Somali politics.

Geeska: Puntland has said it is breaking with the federal government which was predictable. But said it was opened to dialogue if there was a U-turn, what are the odds of that happening?

AIS: In a country where politics is virtually bereft of trust, unilateral action of this nature deepens mistrust between people and regions. Hassan Sheikh may assume that this is a victory for him, but this is a vacuous and empty victory.

I think the people of Puntland, much like the other provinces, have a right to be engaged and consulted in a way that is mutually beneficial, but for Hassan Sheikh to say that the train has left the station and no one can stop it gives a lot of ammunition to these regional governments to tell him to take his train and dump it into the Indian Ocean.

So, one must exercise political maturity, sensible and generous enough to his people to understand as the old Somali proverb says: “dad waxay ku dhaamaan ma jiro, walalo”, the best way to deal with people, is to address them as brothers. The absence of consultation is a shame for the federal government.

Geeska: What does the withdrawal of Puntland portend for the Somali state?

AIS: If you look at every statistic, education, maternal deaths, literacy, health, economy in terms of employment; in every aspect of human and ecological life, Somalia suffers from some of the worst in the world. And so, whether it is Puntland, or Somaliland, Jubbaland or whatever, none of them has the wherewithal to create decent lives for all their people on their own.

If you look at the world more broadly, political institutions are scaling up and becoming bigger and bigger through globalisation, so it is as if these authorities are moving in the wrong direction in history. The reward for that is oblivion. Our people will suffer.

They’ll become clients of the Emiratis and others, turning into supplicants of egregious regimes in the Middle East. They have emasculated the populations in their own countries, and so they cannot respect populations in other countries when they don’t even respect their own.

Geeska: One of the amendments was to restrict the number of parties to three. We’ve seen that elsewhere in Somaliland and Puntland too. What are your thoughts on this measure at the national level?

AIS: One of the tragedies of Somali politics over the last fifty or so years is that there are no competing political ideas that are anchored on people’s hopes about the future. So, whether it is three, four or whatever doesn’t matter in this case. The parties won’t do what they’re meant to, which is to set a political agenda for the country. Platitudes cannot become substitutes for reality and substance.

Geeska: The lack of public input has been a big problem for some observers. There was no referendum either. At the very least irrespective of our assessments of the outcome, it could have been a constitution owned by the Somali people. What could have been done differently here?

AIS: The leaders of the house which represent the provinces could have gone to the people they represent and checked how they feel, allowed them to air their grievances and taken that feedback to parliament, at least.